Part II, taken directly from The Founder’s Bible

The Geneva’s marginal commentaries directly influenced not only the colonists’ views on government but also on subjects such as public education, civil rights, purchasing land from the Indians, instituting free-market economics, creating written documents of governance, reforming corrupt judicial practices, and many other areas. (For more on how the Bible specifically shaped American practices in these areas, see the commentary accompanying Proverbs 18:17, John 17:3, Acts 16:9 and 2 Thessalonians 3:10)

In 1568, English church leaders and supporters of monarchal authority, stringing from the criticism leveled at them in the Geneva’s commentaries, tried to stem the popularity of that Bible by producing the Bishops Bible as a rival edition. It was made the official Bible of the Church of England but never gained popularity among the people. It was the early forerunner of King James Version, and it too, contained the Apocrypha.

In 1582, the first Roman Catholic New Testament was printed in English. Translated from the Latin at a college in Rheims, France, it is thus known as the Rheims. In 1609, the Old Testament and Apocrypha were translated from the Latin at a college in Douai (Douay), France. Combining the two, it became the first printing of a full Roman Catholic Bible in English, known as the Douay-Rheims Version.

In 1604, English clergy from the Church of England asked King James I for a Bible version that would replace the Bishops Bible and rival the scholarship and accuracy of the Geneva, but (understandably) without the Geneva commentaries that so thoroughly excoriated them, including their anti-Biblical “Divine Right of Kings” doctrine. (For more about this story, see “Escape from Tyranny” accompanying Exodus 12, and for more on what the Bible said about this teaching and on when submission to government power is proper, see the commentary with Romans 13.) Fifty scholars therefore convened and consulted a number of earlier versions (including the Tyndale, Coverdale, Matthews, Great Bible, Geneva, and Rheims) in producing their new Bible: the King James Version.

When it rolled off the presses in 1611, it became the official Bible of the realm and was chained to the pulpit of every English church. A policy was also enacted that forbade the printing of any English language Bible in any colony unless with official approval of the Crown, which was not likely to be given for versions such as the Geneva.

Significantly, the King James and the Geneva versions were very similar in their wording (it is estimated that ninety-five percent of the text between the two is the same), but the King James eliminated the hated commentaries and thus silenced a major dissenting voice. Nevertheless, the King James was an excellent and an accurate translation and currently stands as the most-printed book in the world, with over one billion copies published.

In 1661, John Elio of Boston, Massachusetts, printed a New Testament in the Algonquian language (that is, the Massachusetts or Mohican), and in 1663, he printed the full Bible – the first Bible to be printed in America. (For more about John Eliot and this special Bible, see the commentary accompanying Acts 16:9.)

In 1743, Christopher Sauer of Germantown, Pennsylvania, printed a Bible in German, from the Martin Luther translation of 1534. He printed a second version in 1763, but that of 1776 was his most famous. He printed 3,000 copies just prior to the Battle of Germantown in the American Revolution, but the occupying British troops seized most of his Bibles and used them as firewood and bedding for their horses. The British also tore pages from the Bible to use as wadding in their guns, to separate the powder from the lead ball. Only a handful of these Bibles survived the Revolution, and today they are known as “Gun Wad Bibles.”

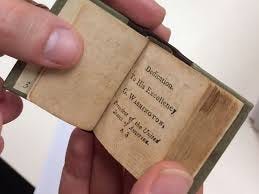

In 1765, America’s first Thumb (or miniature) Bible was printed, being so called because its measurements were a mere 1.3 inches by 1 inch. It was an abridgement of the Bible for children that included many pictures spread of 100+ pages, with six lines per page. The first Thumb Bible had been printed in England in 1601.

Because of the British policy banning English-language Bibles from being printed in America, America had to import Bibles from England. But during the Revolution in 1777, as a result of British blockades, America began experiencing a shortage of several important commodities, including Bibles. On July 7th, a request was place before the Continental Congress to print or import more, because “Unless timely care be used to prevent it, we shall not have Bibles for our schools and families and for the public worship of God in our churches.” Congress concurred with that assessment and announced: “The Congress desire to have a Bible printed under their care and by their encouragement.” However, a special committee overseeing that project found that it would be cheaper to import the Bibles than print them, and therefore recommended:

The use of the Bible is so universal and its importance so great, … your Committee recommend that Congress will order the Committee of Commerce to import 20,000 Bibles from Holland, Scotland, or elsewhere, into the different ports of the States of the Union.

Congress agreed and ordered the Bibles imported. Interestingly, decades later in 1854, when a group claimed that the government was violating the separation of Church and State by allowing government-sponsored religious activities in public, the Chairman of the House judiciary Committee responded with a lengthy report refuting their claims. In so doing, he specifically cited that 1777 act of Congress noting:

On the 11th of September, 1777, a committee, having consulted with Dr. Allison [an early congressional chaplain] about printing an edition of thirty thousand Bibles, and finding that they would be compelled to send abroad for type and paper with an advance of E10,272, 10[over $2 million in today’s currency], Congress voted to instruct the Committee on Commerce to import twenty thousand Bibles from Scotland and Holland into the different ports of the Union. The reason assigned was that the use of the book was so universal and important. Now, what was passing on that day? The army of Washington was fighting the battle of Brandywine; the gallant soldiers of the Revolution were displaying their heroic though unavailing valor; twelve hundred soldiers were stretched in death on that battlefield; Lafayette was bleeding; the booming of the cannon was heard in the hall where Congress was sitting [in Philadelphia] – in the hall from which Congress was soon to be a fugitive. At that important hour, Congress was passing an order for importing twenty thousand Bibles; and yet we have never heard that they were charged by their generation of any attempt to unite Church and State or surpassing their powers to legislate on religious matters.

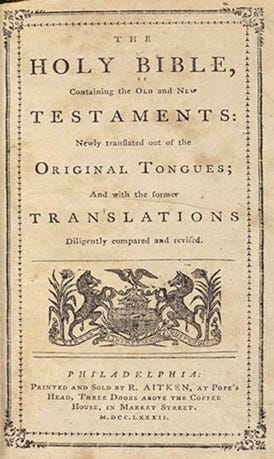

Those Bibles, for whatever reason, were not imported, and as the war prolonged, the shortage recurred. So in 1781, Aitken publisher of The Pennsylvania Magazine and official printer of the journals of the Continental Congress, petitioned Congress for permission to print Bibles on his presses in Philadelphia, thus precluding the need to import them. (In 1777, Aitken had printed America’s first English-language New Testament, reprinting it in 1778, 1779, 1780, and 1781.) Explaining that the new full Bible would be “a neat edition of the Holy Scriptures for the use of schools,” Congress approved his request and appointed a congressional committee to oversee the project. On September 12, 1782 that Bible received the approval of the full Congress and soon began rolling off the presses with a congressional endorsement printed in front. Known as “The Bible of the Revolution,” it was the first English-language Bible printed in America

To be continued…

Facebook: Toni Shuppe on Facebook

Instagram: Toni Shuppe on Instagram

Truth Social: Toni Shuppe on TruthSocial

Gab: Toni Shuppe on Gab

Telegram: Toni Shuppe on Telegram

Fascinating! Thanks, Toni!